Available for Purchase.

"*" indicates required fields

This submission is an inquiry of availability and details but does not guarantee a sale. Thank you for your understanding.

Liz Hager, 20250404

Mixed media on panel, 12 x 12"

Lavender, lilac, plum, periwinkle, eggplant, grape, amethyst, mauve, mulberry. Purple as a category descriptor seems pedestrian by comparison to its offspring, until one learns it derives from the Latin purpura, the Tyrian snail, the subject of a gobsmacking story of ancient world production.

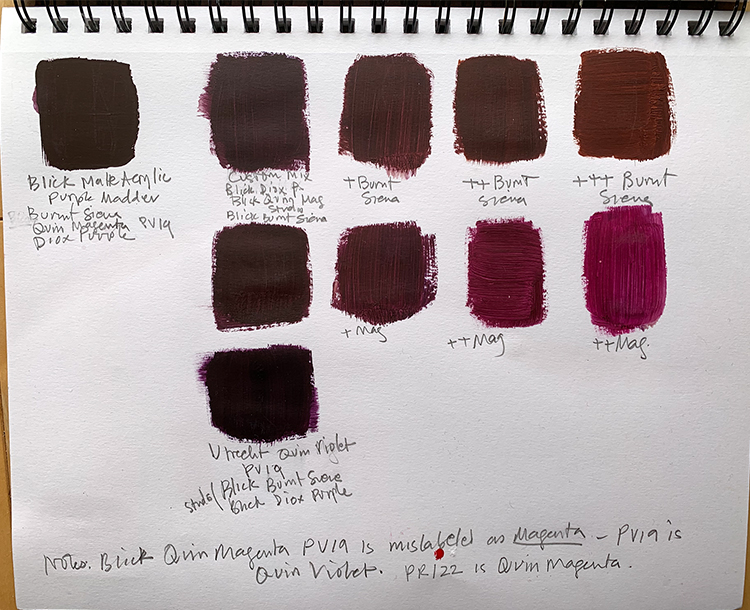

I’m working exclusively in the acrylic medium for the moment, and I am continuously awed by the emotive properties of Blick’s Matte Acrylic Purple Madder, a lush eggplant hue, which (like gouache) dries to a rich dark non- reflective film. Purple madder is a deep pool of mystery, the Edgar Allan Poe of pigments.

What is Purple Madder?

Fine art paint names can be frustratingly confusing, if not downright misleading. Golden’s Quinacridone Red is actually made from PV19-Quinacridone Violet (Color Index Colors). Further, the same manufacturer can process the same raw pigment into a different end color—Golden uses PV19 as the sole pigment in both Quinacridone Red and Quinacridone Violet. The pigment information only matters I think to a painter who, like me, enjoys mixing custom colors.

If an unadulterated Purple Madder pigment exists, I haven’t found it. The few tubes I’ve come across that carry the name are combinations of at least two pigments. Blick uses Burnt Sienna, Quinacridone Magenta and Dioxazine Violet; Windsor & Newton oil paint is made from Imidazolone Brown and Dioxazine Violet; Rembrandt’s Permanent Madder Lake Purple watercolor mixes Pyrrole Rubine with Quinacridone Violet.

Why the funny name?

Like many pigments, purple madder was originally a textile dye. For millennia dyer’s madder was derived by boiling the roots of the herbaceous Rubia tinctorum plant, manipulating the process to create a huge range of shades from brownish to purplish to pinks, bright and bluish reds. The term madder derived from the Old English “mædere,” the common term for Rubia tinctorum, and possibly a linguistic adoption of the Latin ruber or the proto-Indo-European word for dye.

Dyes and paints are kissing cousins. Dyes are soluble in water; pigments, originally derived from dyes, tend to be insoluble in water, and thus are usually mixed with a binder (e.g. fat, seed oil, egg white or polymers in modern times) to produce a coloring substance.

Why is there no pure purple madder pigment?

Purple madder is a natural lake pigment; that is, type of colorant created by combining a dye with a metallic salt and alkali. This solution can be dried into a solid insoluble pigment and added to a binder to produce paint. As is the case with dyes, there is no one purple madder pigment. (Ah ha!)

The earliest examples of madder-based pigments in the ancient world are from Cypriot pottery from the eighth and seventh centuries BCE. Perhaps the most well-known examples of ancient use of purple madder are found in Fayum mummy portraits from 1st century and onwards Egypt, although madder is also found in frescos and mosaics.

Beginning with the discovery of the very alluring purple mauevine in 1856, an explosion of synthetically-produced dyes revolutionized the world of color, and with it, the industrial economy. Artists suddenly had a vast and affordable range of colors not previously available. Industrially-produced paints could be applied to all sorts of new products. As it turns out, the quinacridone reds we now associate with purple madder hue were not synthesized until the late 19th century; dioxazine purple not until in 1928.

So, at the heart of (purple) madder is the Industrial Revolution. My little bottle of Blick Matte Acrylic is a silent reminder of the full-scale transformation from an agrarian to our modern world.

0 Comments